IN RECENT YEARS the British economy has tended to be in the news for the wrong reasons. Growth has been soggy, inflation has been high and living standards have been squeezed. Over the past 15 years productivity growth has stalled and income per person has declined relative to that in many other developed countries. Brexit is one reason. Another is poor policy choices that the government made in response to the financial crisis of 2008-09. The Labour government, elected in July 2024, has made reviving economic growth its top priority.

Relative economic decline is nothing new to Britain. It has been happening since the mid- to late 19th century. As the first country to industrialise in the late 18th century Britain became the richest nation the world had ever seen. Its lead could never last. In the 20th century Britain became the first country to deindustrialise on a large scale. The story of how it achieved primacy, and then lost it, is a fascinating one. What is more, Britain was at the heart of the first great modern age of globalisation before 1914, and was central to the next phase of global economic integration, which began in the 1980s. Many, if not most, of the lessons of British economic history are relevant to the rest of the developed world.

The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. By Robert Allen. Cambridge University Press; 344 pages; $120 and £76.99

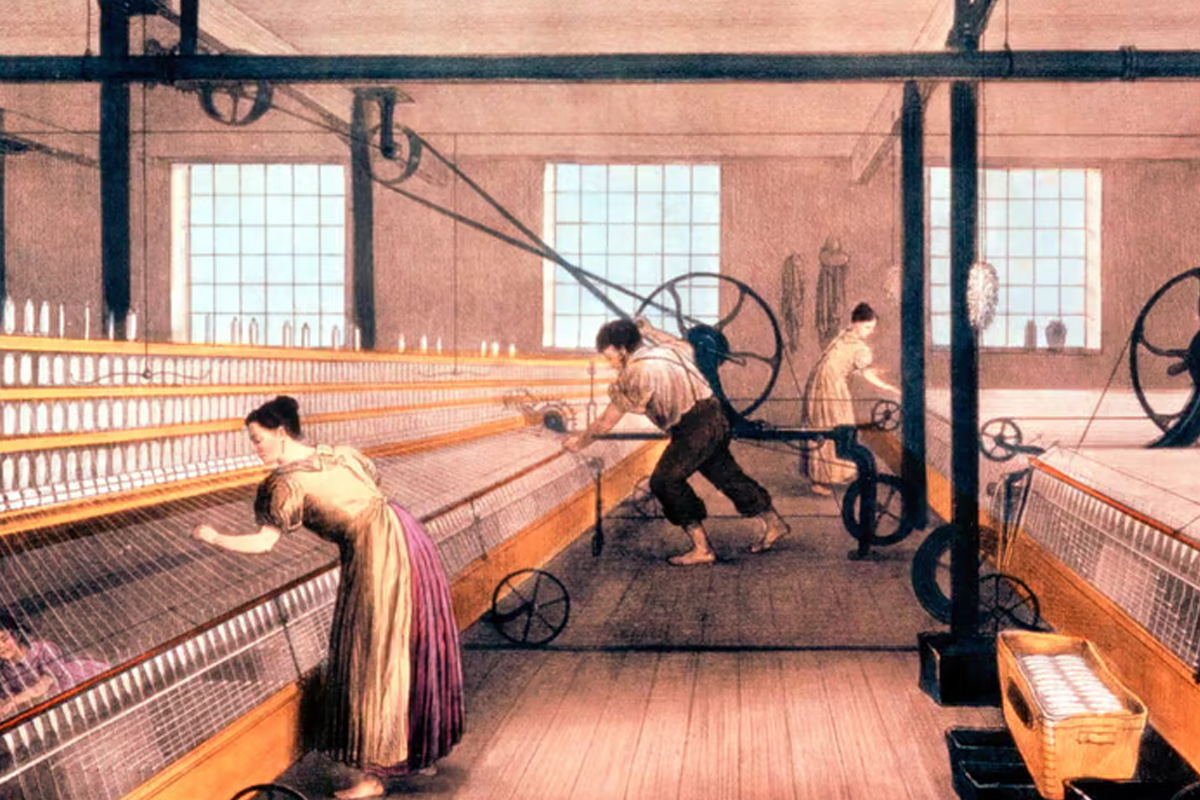

The Industrial Revolution was arguably the single most important process in human history. The birth of modern economic growth—the ability to increase productivity and get more output from a given level of inputs—transformed how people live. In the pre-industrial world living standards tended to move inversely with the size of the population: as the number of people rose but the amount of resources did not, income per person would fall. After the Industrial Revolution that grim calculus changed; both the number of people and their incomes could rise.

Unsurprisingly the nature of this shift and the reasons for it remain the subject of much academic debate. Robert Allen is the leading proponent of one school of thinking, which might be termed materialist. He argues that British entrepreneurs in the late 18th century operated within a unique wage and price structure. Labour was expensive but capital and energy were cheap. It therefore made sense to replace labour with capital. The growth of mills and factories, by this reading, was the simple result of Britain’s cost structure and the incentives this created. As Mr Allen puts it, “the Industrial Revolution, in short, was invented in Britain in the 18th century because it paid to invent it there.”

The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain 1700-1850. By Joel Mokyr. Yale University Press; 576 pages; $40. Penguin; £22

For Joel Mokyr the real driver of the Industrial Revolution is to be found in the realm of ideas. He emphasises the role of the European Enlightenment. This created the modern scientific method, which could produce useful innovations and encouraged a rethinking of institutional structures. Enlightenment ideas, according to Mr Mokyr, led to a reduction in rent-seeking by governing elites and to more competitive markets. At the same time, the spread of Baconian science, a method based on experimentation and the dissemination of results inspired by the mediaeval philosopher Roger Bacon, increased the stock of knowledge. England, and later Britain, was a relatively liberal society in the 18th and early 19th centuries in which ideas and debate flourished. That encouraged productivity-boosting innovations, like the development of railways.

Forging Ahead, Falling Behind and Fighting Back: British Economic Growth from the Industrial Revolution to the Financial Crisis. By Nicholas Crafts. Cambridge University Press; 160 pages; $95 and £75

Nicholas Crafts, who died in 2023, was a leading historian of Britain’s economy. He crammed decades of scholarship into this short book. “Forging Ahead” sets out how, after the Industrial Revolution, the British economy briefly dominated the globe. By the end of the 19th century the new industrial powers of Germany and America were challenging it. Crafts chronicles the years of decline after the second world war and the recovery that began in the 1980s and 1990s. Not many books cover 250 years in fewer than 200 pages without losing crucial details. “Forging Ahead” succeeds, giving readers the best overview of Britain’s economic rise, fall and, in the 1980s and 1990s, rebirth. It is less strong on the second decline of the 2010s.

Goodbye, Great Britain: The 1976 IMF Crisis. By Kathleen Burk and Alec Cairncross. Yale University Press; 256 pages; $65 and £44

The IMF crisis in 1976 is one of the most dramatic episodes in modern British economic history. In that year concurrent domestic and international crises forced the government to seek an emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund to support the value of sterling. The fund demanded that the government fulfil harsh conditions. The catastrophe still resonates. Conservative politicians deride the Labour Party for going “cap in hand” to the IMF. “Goodbye Great Britain”, published in 1992, is the best book on the crisis. Sir Alec Cairncross, a senior government economist for many years, understood the dynamics of policymaking. His co-author, Kathleen Burk, is a historian of international relations who brought to the book her knowledge of how decisions were made in London and in Washington, DC, where the fund has its headquarters. It is especially good on the complex interactions between real-time financial-market developments, economic data and politics in a crisis. Some elements of the book sounded eerily familiar during the short crisis caused by Liz Truss’s mini-budget in September 2022.

Britain in Decline: Economic Policy, Political Strategy and the British State. By Andrew Gamble. Bloomsbury; 263 pages; £41.99

Andrew Gamble’s “Britain in Decline” was published in the 1980s and updated in the 1990s. In many ways, right down to its title, it reflects the state of thinking about Britain in the 1970s. It puts British economic history in the context of political economy. It tells the story of the rise of the industrial and commercial middle class in the 19th century, the entry into power of the new industrial working class in the 20th century and the fightback by capital under Margaret Thatcher beginning in the 1980s. For Mr Gamble, economic developments are ultimately shaped by political coalitions, which themselves slowly shift in response to structural economic changes.

The Rise and Fall of the British Nation: A 20th Century History. By David Edgerton. Penguin; 720 pages; £18.99

David Edgerton’s history of Britain in the 20th century covers politics, society and culture but also has a big economic component. It is revisionist history at its best, politely arguing that the existing consensus on all manner of topics is wrong. Mr Edgerton believes that other historians have exaggerated the decline of the post-war years. It is more a story of European catch-up than of British failure, he writes. He makes the surprising argument that the warfare state has historically been a much bigger deal than the welfare state. Even as late as the 1970s defence expenditure was higher than health spending, Mr Edgerton notes. Perhaps his most interesting idea is that the “British” economy was only truly British between the 1940s and 1970s. What came both before and afterwards was a far more globalised version that cannot be understood without looking outside the country’s borders.

Also try:

Campaigning for the election in July 2024 focused on Britain’s economy. Our coverage of the challenges facing the new government included a leader outlining how the Labour Party could end stagnation, an article about how difficult that will be and a post-election leader urging Labour to be bold in its approach to the economy. Soon after the election we assessed evidence that growth was bouncing back from a recession in 2023. One way to improve Britain’s economic performance, we argued, is to improve the quality of its managers. Our finance and economics correspondent has also written a history of the British economy, “Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through”.

Información extraída de: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-reads/2024/09/03/what-to-read-about-the-british-economy