Britain will aim to convince Donald Trump its services-dominated trade with the United States should escape the worst of tariffs even as it cautiously repairs ties with the European Union and nurtures commercial links with China.

Trump has floated blanket tariffs of 10% to 20% on virtually all imports when he returns to the White House in January and this week pledged big tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China too.

For Britain’s trade-sensitive economy, such threats to global commerce could stymie the dash for higher growth that is a top priority of the Labour government elected in July.

After Brexit complicated ties with the European Union – by far its largest trade partner – Britain believes it has a strong case to preserve and build on a U.S. partnership which already accounts for around a fifth of total UK trade.

While Trump’s anger is targeted at the countries with whom the United States runs a trade deficit, differing methodologies of their respective statistics agencies mean that Britain and the U.S. both report trade surpluses with the other.

Moreover, while Trump tariffs are widely seen as focusing on imported manufactured items – the most high-profile example being German luxury cars – over two-thirds of UK exports to the United States come from services rather than goods.

“I don’t think the criticisms I’ve seen of some European countries in that presidential campaign do apply to us,” Business and Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds told lawmakers this week, adding that Britain would not shy away from making the case for free trade to the Trump administration.

“We should be always willing to be advocates for open, transparent, free trading relationships around the world.”

The goal is to work with Trump while also fixing some barriers to trade with the EU, although one Trump adviser has suggested Britain may have to choose between the two.

While Britain has ruled out rejoining the EU’s single market or customs union, which it left after Brexit, it wants a “reset” in EU ties, and hopes to agree a new veterinary agreement to reduce border checks.

Liam Byrne, chair of the business and trade committee which Reynolds was speaking at, said the government was right to try “to optimise a grand bargain” and balance ties with the United States, Europe and China.

He said that pursuing closeness with the EU might make a fully fledged Free Trade Agreement with the United States less likely, but that an FTA may be a “mirage” compared to less ambitious, sectoral pacts that could be struck to avoid tariffs that were in “nobody’s interest”.

“I think closer ties with the EU gives us more upside faster and I don’t think it completely ends decent cooperation on trade with the United States,” Byrne, a Labour lawmaker, told Reuters ahead of the session.

More than 40% of British exports are to the EU, compared to 22% that go to the U.S., latest government figures show.

Both London and Brussels have hailed a constructive new start under the Labour government while acknowledging talks will be tough, with the EU wanting easier youth mobility to be on the table.

Reynolds highlighted comparable agricultural standards between the EU and the UK as a reason why an agreement to reduce checks on farm and fish products was achievable.

By contrast, he said that lawmakers would “recognise the challenges” of a free trade agreement with the United States. Alluding to disagreements over agricultural standards that have seen previous talks stall, Reynolds said “there would be a pretty profound conversation to have”.

IN A BIND

George Riddell, director of Trade Strategy at consultancy EY UK, said any non-tariff restrictions on services by the United States would cause concern, while firms exporting goods face the prospect of shipments leaving Britain this year that could be subject to a new tariff regime by the time they arrive.

“Businesses are having to scenario-plan at the moment not really understanding what’s going to happen,” he said.

As well as closer EU ties, Britain is indicating an increased openness to working with China, even as Trump threatens to impose tariffs.

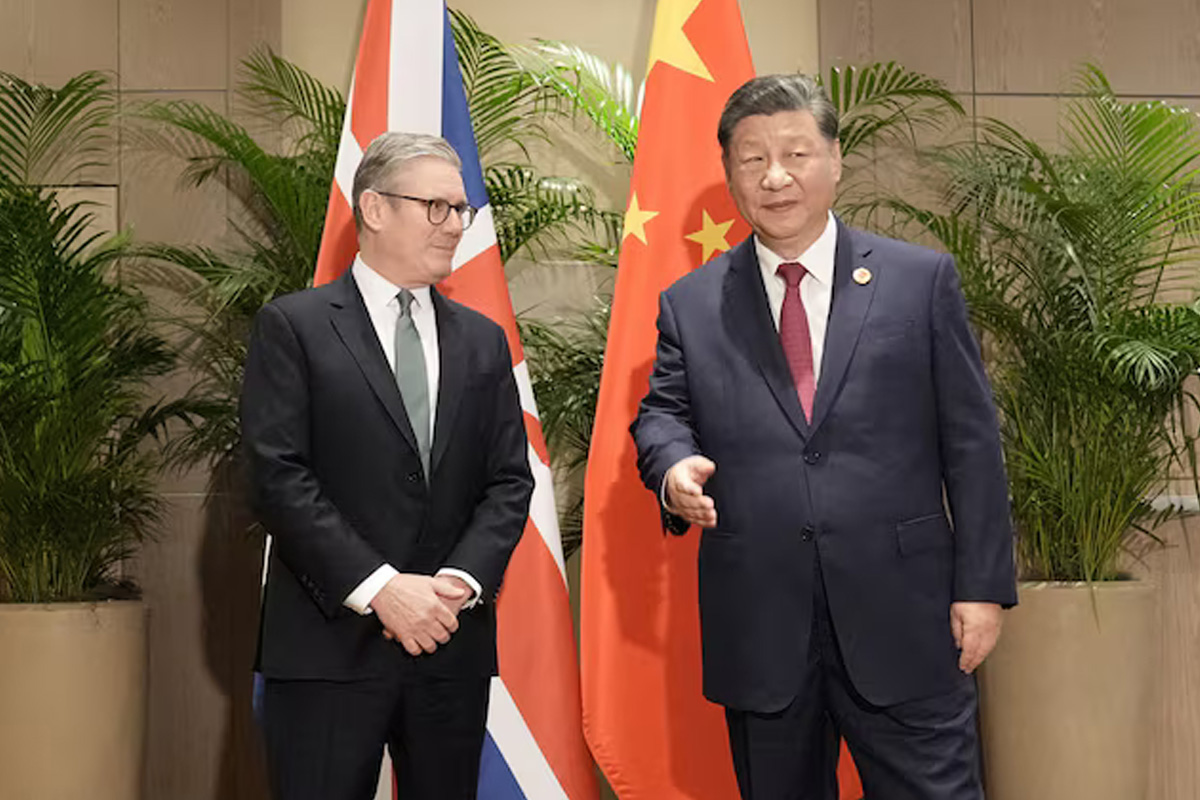

Prime Minister Keir Starmer met President Xi Jinping at the G20 for the first leader-level talks since 2018, while finance minister Rachel Reeves is set to visit Beijing next year.

Britain would find it “exceptionally difficult to play all sides as the competing issues are too diverse,” said Simon Sutcliffe, partner at tax and business advisory firm Blick Rothenberg, adding that London might choose to focus on EU and China ties and ride out potential Trump tariffs.

Byrne said Britain could have “guard rails” on China trade to help protect economic security and U.S. interests, but Sam Lowe, partner at consultancy Flint Global, said Britain’s trade ties with China might irk Trump more than those with the EU.

“I think it’s quite plausible that Donald Trump tells the UK to impose new tariffs or trade restrictions on China in return for concessions from the U.S.,” he said. “And that will put the UK in a bind, undoubtedly.”

($1 = 0.7937 pounds)

Información extraída de: https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-charts-tricky-trade-course-trump-threatens-tariffs-2024-11-28/