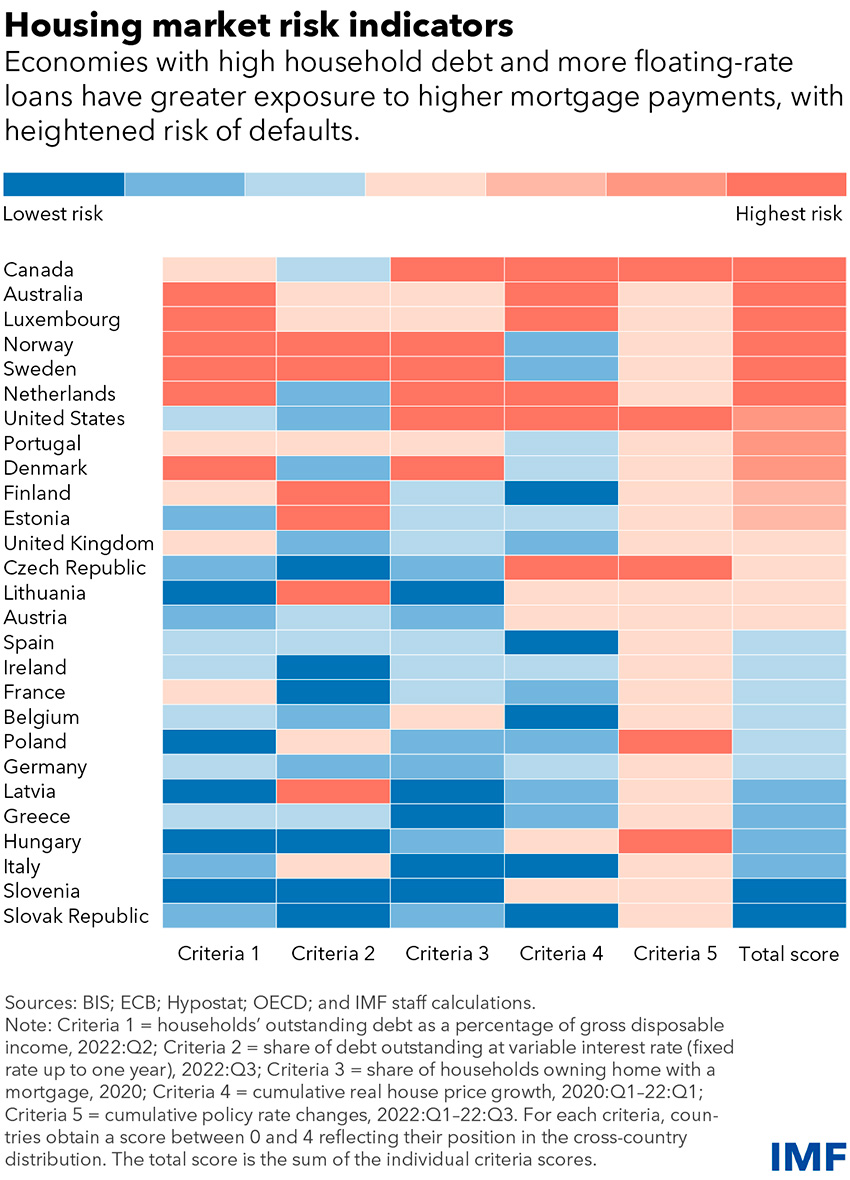

Countries with elevated housing prices and high household debt issued at floating rates are particularly vulnerable to monetary policy tightening.

The pandemic propelled housing prices to record levels in many countries, especially advanced economies, amid low interest rates and tight property supplies. Then prices started falling late last year in many countries, while others saw the pace of gains slow.

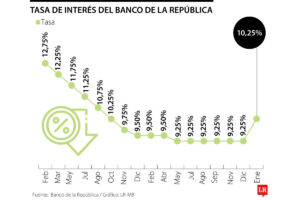

The deterioration was more pronounced in advanced economies with signs of stretched valuations before and during the pandemic. With central banks raising interest rates to contain inflation, the average mortgage rate reached 6.8 percent in advanced economies in late 2022, more than doubling from the start of last year. Now, if borrowing costs keep rising or remain elevated for longer, demand and prices are likely to weaken further.

As the Chart of the Week shows, countries with high levels of household debt and a large share of borrowing issued at floating rates are more exposed to higher mortgage payments resulting in a higher risk of defaults. Canada, Australia, Norway, and Sweden are at greatest risk, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group of 38 mostly advanced economies.

On the upside, in countries where housing prices grew rapidly, price declines in the runup to the current monetary policy tightening cycle could improve affordability—as we outlined in the World Economic Outlook published in April.

Meanwhile there are important differences between current conditions and the global financial crisis a decade and a half ago. In most cases, while it is unlikely that falling home prices will spark a financial crisis, a sharp drop in house prices could dim the economic outlook. And the build-up of vulnerabilities warrants close monitoring in coming years—and possibly even intervention by policymakers.

Banks are better capitalized than before the global financial crisis, and underwriting standards in many advanced economies are tighter today than before the crisis.

However, the average household debt-to-income ratio across countries is about the same as in 2007, driven mainly by households in economies that managed to escape the brunt of the global financial crisis and have since run up substantial borrowing.