With appropriate policies and improved productivity, Europe can reconcile short-term wage pressures and long-term labor trends with less inflation.

Europe’s economic recovery is getting a much-needed boost from rising wages and higher incomes. But in countries where population aging is shrinking the workforce, policymakers may soon face new challenges. Short-term wage pressures could combine with longer-term tightness in labor markets to stoke inflationary pressures.

After two years of falling purchasing power, it’s not surprising that Europe’s workers are pushing for more pay. Nominal wages rose by 4.5 percent in the euro area and more than 10 percent in other parts of Europe in the first half of this year. Higher wages help alleviate cost-of-living pressures and support economic expansion.

But improved productivity, coupled with tight macroeconomic policies which limit companies from passing on higher costs to consumers, are essential if economies are to afford much higher wages without fanning inflation, as discussed in our latest Regional Economic Outlook.

Wage growth has differed across countries. Across much of Europe’s advanced economies, wages have further to rise before they catch up with prices, meaning that pressure for pay rises is likely to persist. In Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe, wage growth has been more rapid and kept up with prices. This region has seen high wage growth in the past, but back then productivity growth was strong as well. Today it is weak. That means further high pay rises would chip away at competitiveness.

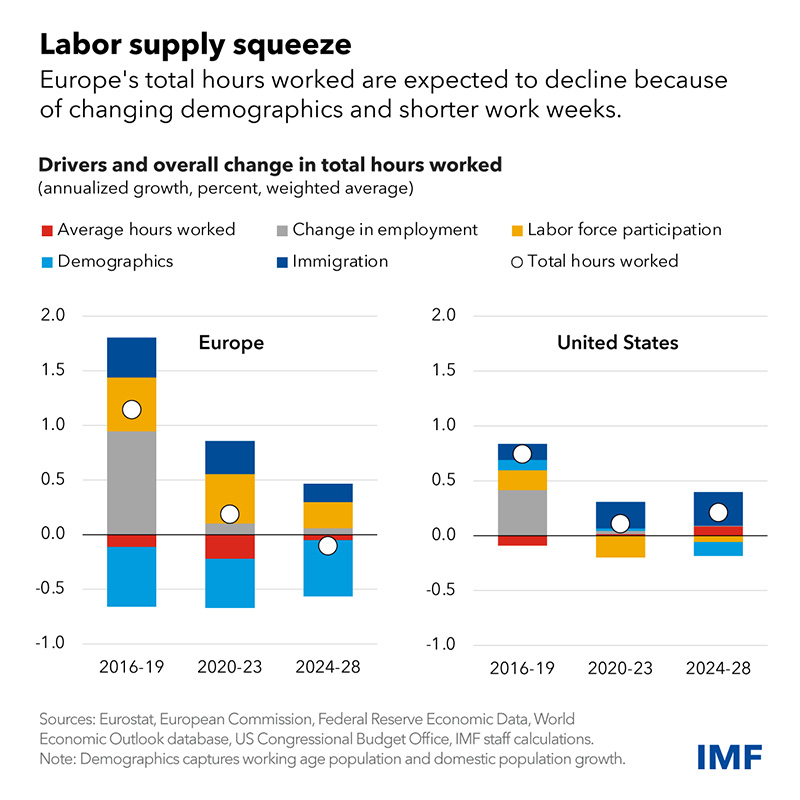

Wage pressures are unlikely to subside any time soon. As the Chart of the Week shows, longer-term trends are already squeezing labor supply (total hours worked). Demographics and shorter working weeks mean employers face fierce competition to find qualified workers and must pay more to retain them.

Over the past decade, Europe’s labor force participation grew relatively rapidly. Even if this trend continues, the labor supply could decline by 0.1 percent annually over the next five years as the population ages, population growth slows, and the shortening of working weeks continues. By contrast, the US labor supply is expected to grow by 0.2 percent as immigration and longer working hours more than compensate for a deterioration in demographics.

The scope to offset these labor market trends in Europe is limited. Proposals to increase retirement ages further may run into political opposition. There is also little scope to increase average working hours because shorter work weeks are gaining popularity.

What must policymakers do? There is a fine line between aiding economic recovery and banishing stubbornly high inflation. Central banks must watch for upside risks to inflation and closely monitor wage settlements and their consistency with productivity trends. A marked divergence would be worrisome. The mix of monetary and fiscal policy should remain appropriately tight to bring inflation back to target.

At the same time, structural reforms to increase productivity are becoming critical. Doing so would both lower inflationary labor-market pressures and raise longer-term economic growth potential. Boosting the labor supply by allowing workers to work more hours, making it simpler to transition between jobs, equipping new generations for future jobs, reskilling workers, and facilitating the integration of migrant workers all have an important role to play.