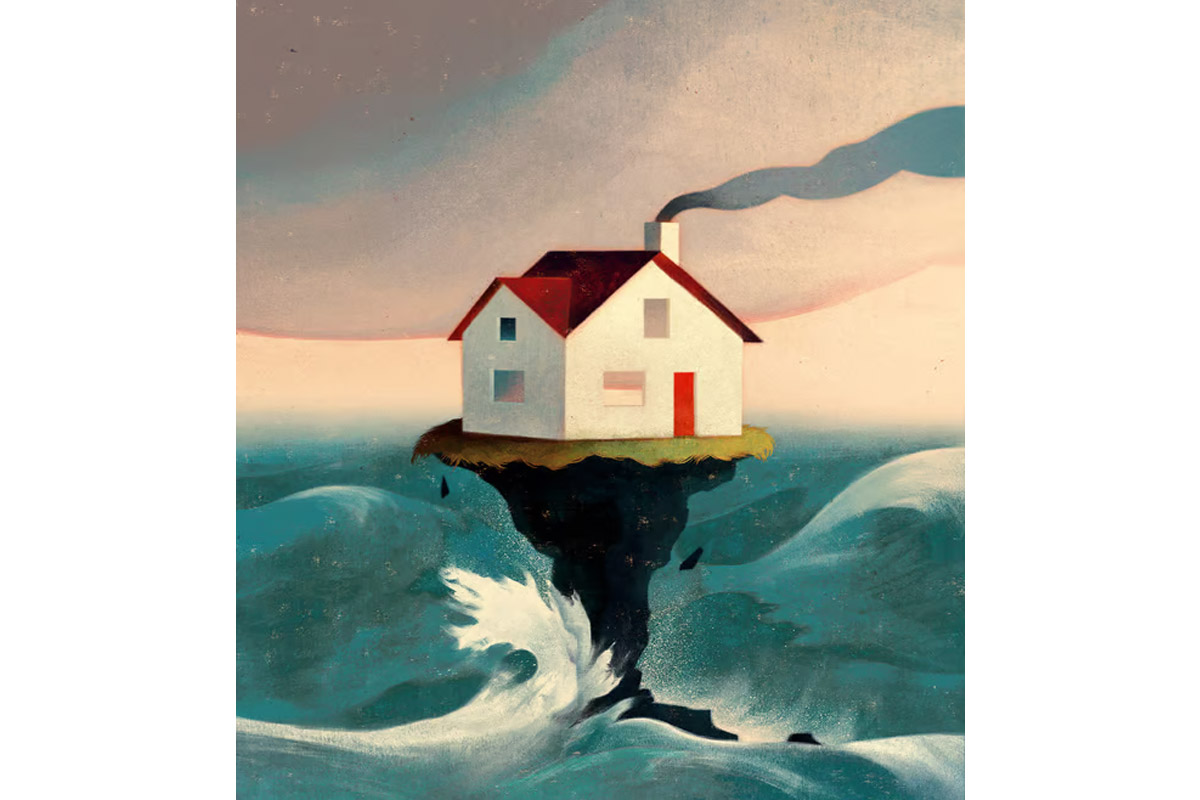

Think about the places vulnerable to climate change, and you might picture rice paddies in Bangladesh or low-lying islands in the Pacific. But another, more surprising answer ought to be your own house. About a tenth of the world’s residential property by value is under threat from global warming—including many houses that are nowhere near the coast. From tornadoes battering midwestern American suburbs to tennis-ball-size hailstones smashing the roofs of Italian villas, the severe weather brought about by greenhouse-gas emissions is shaking the foundations of the world’s most important asset class.

The potential costs stem from policies designed to reduce the emissions of houses as well as from climate-related damage. They are enormous. By one estimate, climate change and the fight against it could wipe out 9% of the value of the world’s housing by 2050—which amounts to $25trn, not much less than America’s annual gdp. It is a huge bill hanging over people’s lives and the global financial system. And it looks destined to trigger an almighty fight over who should pay up.

Homeowners are one candidate. But if you look at property markets today, they do not seem to be bearing the costs. House prices show little sign of adjusting to climate risk. In Miami, the subject of much worrying about rising sea levels, they have increased by four-fifths this decade, much more than the American average. Moreover, because the impact of climate change is still uncertain, many owners may not have known how much of a risk they were taking when they bought their homes.

Yet if taxpayers cough up instead, they will bail out well-heeled owners and blunt helpful incentives to adapt to the looming threat. Apportioning the costs will be hard for governments, not least because they know voters care so much about the value of their homes. The bill has three parts: paying for repairs, investing in protection and modifying houses to limit climate change.

Insurers usually bear the costs of repairs after a storm destroys a roof or a fire guts a property. As the climate worsens and natural disasters become more frequent, home insurance is therefore getting more expensive. In places, it could become so dear as to cause house prices to fall; some experts warn of a “climate-insurance bubble” affecting a third of American homes. Governments must either tolerate the losses that imposes on homeowners or underwrite the risks themselves, as already happens in parts of wildfire-prone California and hurricane-prone Florida. The combined exposure of state-backed “insurers of last resort” in these two states has exploded from $160bn in 2017 to $633bn. Local politicians want to pass on the risk to the federal government, which in effect runs flood insurance today.

Physical damage might be forestalled by investing in protection in properties themselves or in infrastructure. Keeping houses habitable may call for air conditioning. Few Indian homes have it, even though the country is suffering worsening heatwaves. In the Netherlands a system of dykes, ditches and pumps keeps the country dry; Tokyo has barriers to hold back floodwaters. Funding this investment is the second challenge. Should homeowners who had no idea they were at risk have to pay for, say, concrete underpinning for a subsiding house? Or is it right to protect them from such unexpected, and unevenly distributed, costs? Densely populated coastal cities, which are most in need of protection from floods, are often the crown jewels of their countries’ economies and societies—just think of London, New York or Shanghai.

The last question is how to pay for domestic modifications that prevent further climate change. Houses account for 18% of global energy-related emissions. Many are likely to need heat pumps, which work best with underfloor heating or bigger radiators, and thick insulation. Unfortunately, retrofitting homes is expensive. Asking homeowners to pay up can lead to a backlash; last year Germany’s ruling coalition tried to ban gas boilers, only to change course when voters objected to the costs. Italy followed an alternative approach, by offering extraordinarily generous, and badly designed, handouts to households who renovate. It has spent a staggering €219bn ($238bn, or 10% of its gdp) on its “superbonus” scheme.

The full impact of climate change is still some way off. But the sooner policymakers can resolve these questions, the better. The evidence shows that house prices react to these risks only after disaster has struck, when it is too late for preventive investments. Inertia is therefore likely to lead to nasty surprises. Housing is too important an asset to be mispriced across the economy—not least because it is so vital to the financial system.

Governments will have to do their bit. Until the 18th century much of the Netherlands followed the principle that only nearby communities would maintain dykes—and the system was plagued by underinvestment and needless flooding as a result. Governments alone can solve such collective-action problems by building infrastructure, and must do so especially around high-productivity cities. Owners will need inducements to spend big sums retrofitting their homes to pollute less, which benefits everyone.

Wie het water deert

At the same time, however, policymakers must be careful not to subsidise folly by offering large implicit guarantees and explicit state-backed insurance schemes. These not only pose an unacceptable risk to taxpayers, but they also weaken the incentive for people to invest in making their properties more resilient. And by suppressing insurance premiums, they do nothing to discourage people from moving to areas that are already known to be high-risk today. The omens are not good, even though the stakes are so high. For decades governments have failed to disincentivise building on floodplains.

The $25trn bill will pose problems around the world. But doing nothing today will only make tomorrow more painful. For both governments and homeowners, the worst response to the housing conundrum would be to ignore it.